where are the in-betweens?

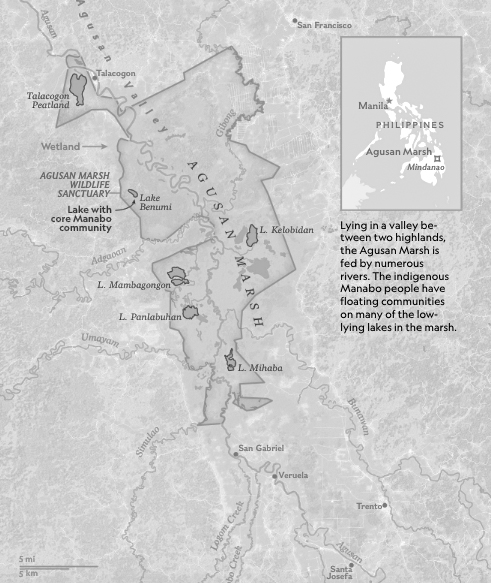

The Guardians of the Marsh is an immersive multi-stage project of the Philippines’ largest wetland, the Agusan Marshlands. A complex vast ecologically significant temporal landscape made up of hundreds of lakes, meandering rivers, boggy swamps, and mystical peatlands, now facing the relentless brunt of the climate crisis. This neglected and forgotten wetland jewel of Asia rapidly shrinks due to climate change and intense socio-economic activity. Severe typhoons, prolonged droughts, torrential flooding, unsustainable agriculture, and illegal logging threatens this wetland frontier.

Left to fade in today’s changing climate and society, this project tells a two-part story of dualities. The wet and the dry, and of future and of past— a story of the neglected wetland through qualitative exploration, quantitative assessment, science-based storytelling, and on-ground initiatives to conserve the landscapes, cultlure, wildlife, and biodiversity within the changing seasons influencing the life of the indigenous and local communities facing the naturecultural issues of its temporal waters.

A sense of place, of time, and of community.

In 2019 and 2020, a recorded total area of more than 100-hectares of peatlands and swamp forests,

or the size of roughly 140 football fields were burnt down to expand palm oil plantations. Prolonged droughts have been exacerbated by the drying climate,

making the peatlands more vulnerable to these fires.

A CULTURE AT RISK

Six municipalities and 38 towns depend on the Agusan Marshlands for livelihood,

water, and food, such as the Manobo indigenous community, who serve as the guardians of the marsh.

Lake Panlabuhan is a major catch basin to prevent massive flooding downstream

to the major city of Butuan in the Philippines

It is now the beginning of the end of their way of culture and life. Instead of rain, there were ashes.

Instead of a stream, there is drought. Instead of water, there is blood.

Marites Babanto, the indigenous woman leaders of the Manobo Tribe has no choice left but to fight

and protect the waters, trees, and peat of her floating community and

the future indigenous generations, who will be inheriting the Agusan Marshlands

that have been passed on by her ancestral forefathers.

INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE BASED SOLUTIONS

As currents turn to indigenous knowledge as an essential solution for climate action—

the Manobo indigenous knowledge and culture is integrated and recognized as science through modern contemporary design within neigboring communities

as means of adaptation to unprecedented extreme weather events such as severe droughts and floods wrought by the ongoing climate crisis.

Floating houses, churches, and schools are designed on rafts anchored to endemic “bangkal” trees

adapting to the changes of water level during drought and flooding.

in the in-betweens

of water and land, of future and past—

the way forward is indigenous.

Read the full story on National Geographic

Published:

National Geographic Explorer Magazine

National Geographic Alamanac 2023

The Manila Times

BBC Future

Mongabay

Exhibitions and Other Media:

Follow the Water, Emerging Islands

ICOMOS Scientific Symposium 2021

WWF Kagubatan Virtual Forest Exhibit

Japan Science Agora 2020

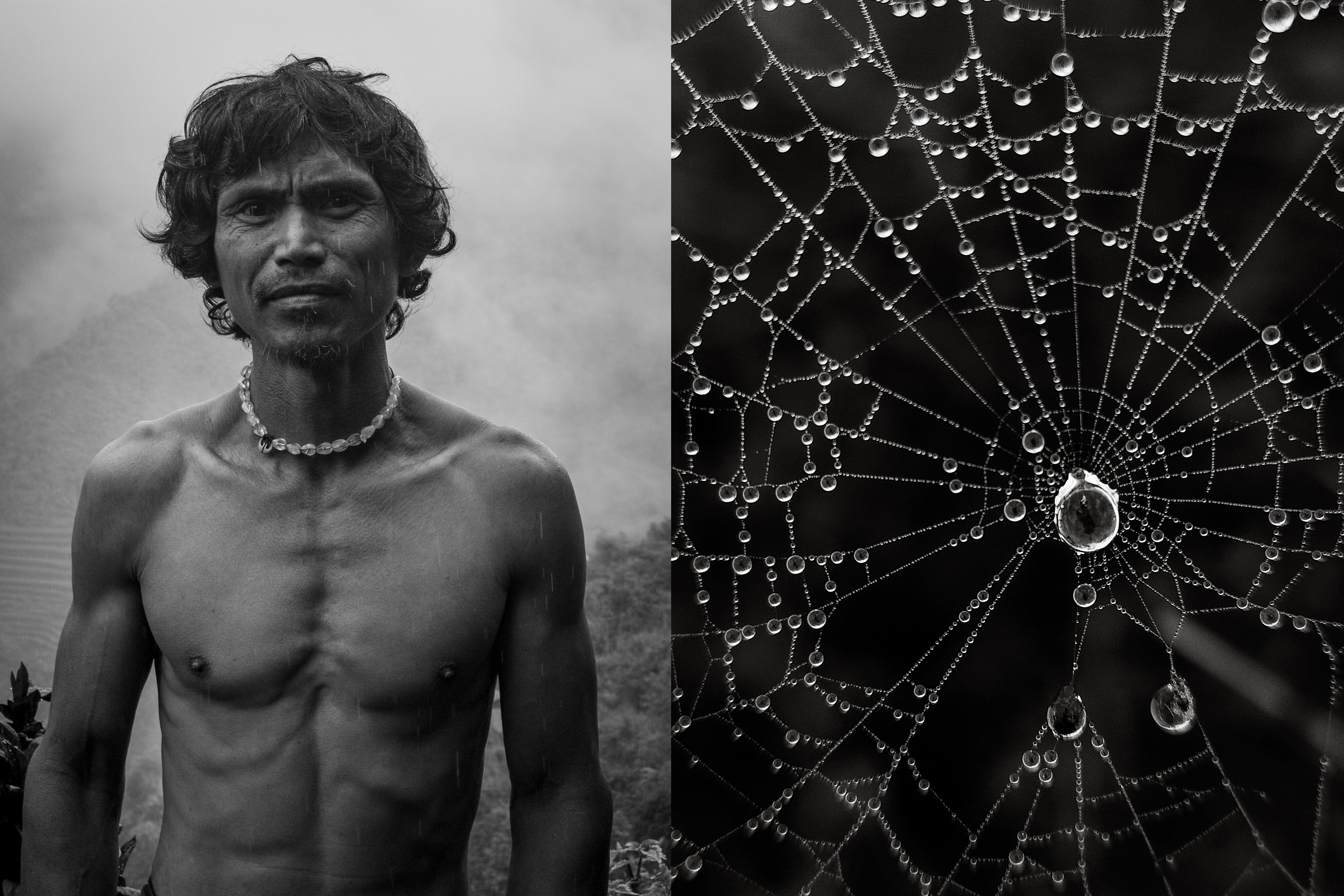

Are there borders, such boundaries, where nature ends and humanity begins, or so, where does man end and nature begins?

As we face the ecological crisis and major biodiversity loss— the wildlife habitats, natural ecosystems, and engines we depend on begin to collapse.

The very fabric of our cities, our livelihoods, and the wildness of our nature crumble with its end.

The Animals We Are is an investigation and reimagination of the wild. To see anew, the beasts inside and outside of us, ultimately constrained within the ecological and social spatial boundaries that transcend evolutionary biology and anthropomorphism, but the living spaces we render and navigate in— the forests, the wetlands, the oceans, the mountains, the cities, and the values we’ve built upon.

For it begins in the paradox of the human condition—

beyond the duality of life itself.

We kill to survive. We destroy to create. We demolish to build.

We die to be reborn.

This paradox of our contradicting reality, where separation and disconnection, rifts from the natural world.

Man against nature. Nature against God. Predator and Prey.

Eco versus Ego. Mind against Bodies.

Where are the lines drawn, and where should these be blurred?

through life, death, and reconnection.

After many months, even years, it is as if the storm had just passed yesterday. Looking back within and after the beating of a storm’s eye,

Super Typhoon Rai or locally known ‘Odette’ is the strongest typhoon that struck in the year 2021, only a few days before Christmas Eve.

The Philippines is one of the countries most impacted by the climate crisis with an average of 20 typhoons crossing its islands annually.

The onslaught of super-typhoons in the Philippines have not only wreaked momentary physical destruction,

but cyclones of emotions within

a sea of compounding trauma and fear within coastal communities.

Who do they call on, when these storms have left their scars?

Who are

these “gods” in which they try to seek salvation?

Wrapped within their thoughts and tides that surround their home of an archipelago,

are

they survivors or mere victims of an insidious cyclic system amid the tides in which they depend on?

Coastal communities build and rebuild

after every passing of a storm, only to be capitalized by a recurring system of disaster and loss,

a creation of messianic myths upon their

respective leaders and corporations as their sole constituents,

indebted in these so-called gods with votes, debts, and loyalty, who “rebuild”

their homes.

These acts of god, these storms amid the climate crisis, where can they be summoned, and who holds them accountable?

Read the Stories: Atmos Magazine |Art Partner CreateCOP | Photo VOGUE | SLEEK Magazine | Collater.al Italian Magazine

land and environmental defenders were killed in the Philippines from 2012 to 2021,

accounting to almost half of the injustices in the world along with Brazil and Colombia.

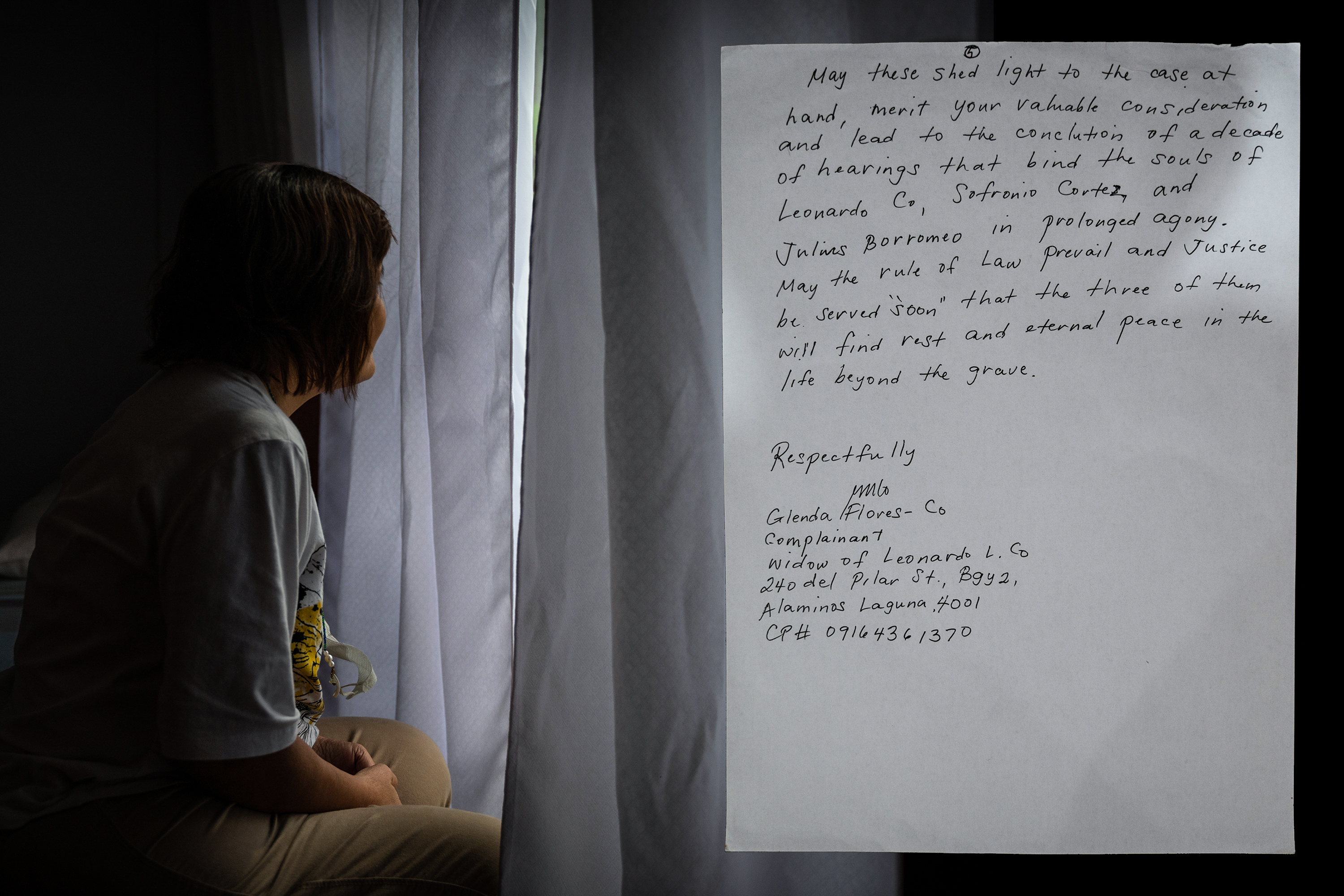

November 15, 2010

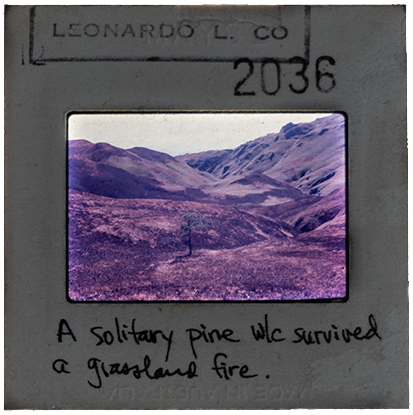

Leonard Co (botanist), Sofronio Cortez (forest guard), and Julius Borromeo (forest guide) were murdered by the army on the roots of a Tanguile tree as they were conducting botanical research for the conservation of the rainforests in Leyte, Philippines.

Linnaea Co, named after a twinflower (Linnaea borealis) is the bereaved and sole daughter of slain botanist Leonard Co. She continues to process her grief since the muder of her father

when she was just 8-years old.

She homes a tree nursery in honour of her father’s botanical legacy, planting wildlings across reforestation sites where her father used to bring her.

![]()

how many more flowers?

how many more years?

how many more in this thirst for justice?

Teresita Borromeo, 56, the widow of slain forest guide Julius Borromeo, revisits the roots of where her husband was murdered in Kananga, Leyte.

She works as a farmer to provide for her five bereaved children as a single mother in a decade’s worth in search for justice.

‘A tree is born, a tree dies, the forest lives forever’

—Leonard L. Co

‘A tree is born, a tree dies, the forest lives forever’

—Leonard L. Co